When time stood still by Yousaf Salahudin

When time stood still by Yousaf Salahudin

Originally published for Dawn in 2004 [archived now], hence reproduced under Creative Commons.

“I was dining with friends at my home when Shaukat Aziz, the finance minister, mentioned to me that the Quaid-i-Azam’s daughter and her family were due to visit Pakistan during the Pakistan-India cricket series. I could hardly believe that. The rest of the dinner passed in a haze while I wondered what it would be like to meet this remarkablelady.

I grew up in a family where stories of the Quaid were often narrated and listened to in rapt attention. I never had the opportunity of meeting the great man himself, even though he seemed omnipresent in our house.

My maternal grandfather, Allama Mohammad Iqbal, gave the vision of Pakistan and when the Mr Jinnah left Congress and settled down in England, it was he who convinced the Quaid that a separate homeland for Muslims was absolutely necessary. The Allama also convinced the Indian Muslims that the Quaid was the only one who could achieve it.

It is quite simple really – had there been no Quaid, there would have been no Pakistan. When they met for the last time at Allama Iqbal’s house shortly before his death in 1938, Iqbal told his son that a gentleman would come to see him that day and that he should be well-dressed and look for an opportunity to get his autograph. Dr Javed Iqbal relates the story in his book Zinda Road. He went into the room where he was sitting. After wishing the great leader, he requested him for his autograph. While signing the book, the Quaid asked him if he wrote poetry like his father did to which he replied in the negative. The Quaid then asked him what he wanted to do when he grew up. The young man didn’t have an answer to that. Mr Jinnah then

asked Allama Iqbal why was his son was silent, to which the poet said: “He is looking at you for advice.”

On my father’s side, our first contact with the League began as far back as 1906 when the League was not a political party but a movement of like-minded people. During the second session in Karachi, my grandfather’s younger brother and cousin attended as representatives of our family. By that time, our family had already started a movement on the lines of Sir Syed to educate underprivileged Muslims in the Punjab. A group of well-to-do Muslims donated their time, money and property for this cause and my great, great grandfather, Mian Karim Buksh, was made life vice-president. It was this institution that built the Islamia College, Railway Road, Islamia College Civil Lines and Islamia College for Women, along with other educational

institutions and orphanages. The Anjuman Himayat-i-Islam, as it came to be known, would hold an annual congregation of Muslims from all over India every year. Smaller sessions were held at the Haveli Baroodkhana which hosted dignitaries such as Altaf Hussain Hali, Deputy Nazir Ahmed, Maulana Shaukat Ali and Maulana Mohammad Ali Jauhar. It was this platform that the Quaid used to address the Muslims of Punjab for the first time. And in 1940 when the Pakistan Resolution was passed, the Quaid entrusted my grandfather, Mian Aminuddin, with the task of organizing and holding the meeting. Mian Aminuddin was chairman of the ‘pindal committee.’

Coming back to the present, the possibility of seeing the Quaid’s daughter in this same haveli moved me beyond words. I didn’t know very much about Dina Wadia other than that she was a private person. I had only read one interview of hers which was done for a documentary by my friend Sophie Swire during the 50th independence celebrations of India and Pakistan. I could clearly see her father in her. I once asked my late mother-in-law, Begum Iftikharuddin, who knew both Jawaharlal Nehru and the Quaid closely, what was the difference between the two.

She said that Nehru had an undeniable presence which one felt the moment he entered a room, but when the Quaid walked in, his presence was simply electrifying. I wondered if his daughter had the same kind of personality.

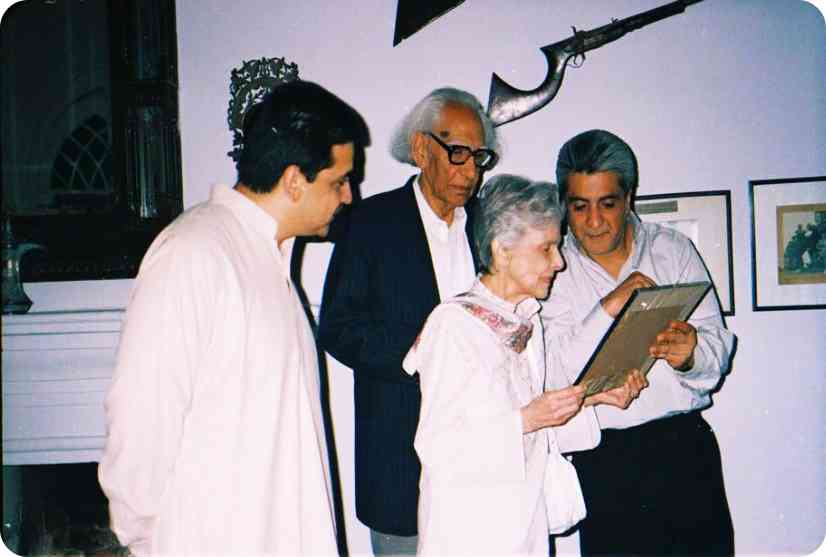

I met Mr Jinnah’s grandson Nasli Wadia and his sons, Ness and Jay, at my house on the evening of March 24 at a party hosted by my son, Jalal. I told Nasli of my overwhelming desire to meet his mother.

The next day, Nasli called to tell me that they were postponing their departure to Karachi and that he would be happy if I joined him and his mother at a chic cafe in the walled city where they were to dine with their friend Shaharyar Khan and his family. After the initial excitement died down, I noticed that Nasli, who had all the amenities of the State Guest House at his disposal, had called me from his own mobile phone. It was typical of what one had heard of the Quaid.

I arrived early at the cafe and was there to watch Ms Wadia walk in. I was stunned by her resemblance to her father. Everyone who sees her for the first time is struck by her remarkable likeness to her father. Shaharyar Khan was kind enough to ask me to sit next to her. When I was able to speak, the first thing I said to her was: “Ma’am, you have done a great honour to us by coming to Pakistan.” To which she replied: “I’m happy to be here but you really must thank Shaharyar. It was on his invitation that I am here.”

A smorgasbord of Lahori specialities was relentlessly delivered to our table. Though I was apprehensive of the assault on her taste buds, she tried a bit of everything and was gracious in praising the food. She then spoke highly of the ambience of the Old City and the Badshahi Masjid. She told me that she had visited my grandfather’s grave earlier that day. I felt somewhat guilty for monopolizing the guest of honour, but I couldn’t help speaking to her. I talked about her father and she listened with great interest. One could clearly see that she loved her father very much. It was amazing not only how closely she looked like her father, she also spoke like him. We were sitting near the stairs leading up to the rooftop and people came and went past us now and again. Out of these people, three women spotted Dina and hesitantly made their way over to her. One tried to speak, but was clearly choked up. After apologizing profusely for interrupting the dinner, she said: “I don’t have words to speak to you. God bless you.”

As we were leaving the cafe, I met my old friend Haroon Rashid with his family. I introduced him to Ms Wadia and said his grandfather, Sir Abdul Rasheed, was the first chief justice and swore in the Quaid as the first governor-general of Pakistan. Confusing Haroon’s name with the Haroon family, she said, “Of course I know the Haroon family, they were friends of my father.” Or maybe she knew his aunt was from the Haroon family. The genuine emotion was overwhelming and I had to take a minute to compose myself before asking her if she would do me the honour of visiting my home. She agreed and I can say without reservation that that was the greatest moment of my life.

I have in the past had the good fortune of entertaining dignitaries, celebrities and heads of states, all of which paled into insignificance when compared with this experience. We all made our way over to my house where I showed her the pictures I had of her father and our families. She looked at all of these pictures with great affection, particularly at one of “Auntie Fatima”, pictured with my mother when she visited the Allama house in 1951. She looked at the pack of cigarettes which I was holding, and said: “Stop smoking. It’s not good for your health.”

“I am trying to, Ma’am,” I said. “Well stop it then, I am ordering you,” she said firmly.

After the haveli, we went for dessert to a restaurant. She invited me to sit in her car, making queries about the landmarks as we passed them by, particularly Data Darbar, the facade of which she admired. The restaurant was, as always, abuzz with young Lahoris enjoying an evening out. There was a large contingent from Lums and some students, on recognizing her, came forward to ask if they could shake her hand.

She graciously shook hands and spoke to them, wishing them luck. It was heartening to see such reverence in the eyes of Pakistan’s so-called disrespectful youth. I don’t think anyone who met Ms Wadia will ever forget her. I opened the door of the car and said goodbye. She kissed me on both cheeks and held my hand firmly. It was an inexplicable sense of reassurance and comfort, this contact with the Quaid’s living link. A small crowd had gathered outside her car. A boy on the street tried to approach her but was stopped by a policeman. “No, no,” she roared, in her father’s voice, “let him come”, and motioned towards him. Like her father, she disliked police escorts and the attendant fanfare. In awe-truck silence, the boy came to the car

where she took his hand, in her usual style with both hands. The people standing around him also followed. There was complete silence as I saw, for the first time ever, a group of Pakistanis forming an orderly queue and waiting for their turn to shake hands with her.

The car rolled away and the evening was at an end. As I stood there and watched her go, I could not help saying to myself: “Thank you, Shaharyar Khan, you have served your country well but surely this was your greatest achievement and thank you, General Pervez Musharraf, for giving her the honour and respect she so deserves. Goodbye, Ma’am, and God bless you. Come back soon, this is the home of your father and you remind us so much of him.

It was over as soon as it had begun, this unimaginable encounter, the most magical evening of my life.”

Yousaf Salahudin