The Basanti Dye – By Y. Saeed

The Basanti Dye – Y. Saeed

The entire north India wakes up from the chilly winter. Its spring here again. The yellow of mustard flowers covers miles on end. It is now that the festival of Basant will be celebrated. There will be singing and dancing,

and beautiful colours everywhere. But it may come as a surprise to many people that a large number of North Indian Muslims will celebrate Basant Panchmi, just like Hindus will.

How Basant came to be celebrated by the Muslims is an interesting story. Apart from the fact that those who had migrated from Central Asia must have brought with them colourful memories of Spring being celebrated with much fanfare in their original homelands, it was the Chishti Sufis who may have begun the celebration of Basant amongst Indian Muslims. The legend goes that 12th Century Chishti Saint Nizamuddin Aulia of Delhi was once so grieved because of the passing away of his young nephew Taqiuddin Nooh, that he withdrew himself completely from the world for a couple of months either locked inside his room or sitting near his nephew s grave. His close friend, disciple and famous court poet, Amir Khusro, who could not bear with his pir s absence any longer, started thinking of ways to brighten him up.

One day Khusro met a few women on the road who were dressed up beautifully, singing and carrying colourful flowers. He asked them what they were up to. The women told him it is Basant Panchmi today, and they are taking the offering of Basant to their god. Khusro found this very fascinating, and smiling he said, “well, my god needs an offering of Basant too”. Immediately, he dressed himself up like those women, took some mustard flowers and singing the same songs, started walking towards the graveyard where his pir would be sitting alone. Nizamuddin Aulia noticed some women coming towards him – he could not recognize Khusro. On close inspection he realized what was going on, and smiled.

That was it. They had all been waiting for him to smile for two months. The entire atmosphere went ecstatic. Other Sufis and disciples too started singing Persian couplets in praise of spring, and symbolically the mustard flowers were offered to the grave of Nooh. Following are some of the Persian lines that they may have sung :

Ashk rez aamad ast abr-e-bahaar

Saaqia gul barez-o-baada beyaar

Or Hindi couplets like :

Sakal bun phool rahi sarson

Ambva borey, tesu phooley, koyal boley daar daar,

Aur gori karat singhar, malania garhwa le aayin barson

Sakal bun phool rahi sarson

The impact of this incident was such that the celebration of Basant became an annual affair in the Khaneqah (monastery) of Nizamuddin Aulia, and subsequently in other centres of Chishti order all over the country. The local Muslims affiliated to all those Dargahs and Khaneqahs automatically took to the tradition of celebrating Basant.

This tradition had probably evolved into a major public festival in the Mughal period. Maheshwar Dayal in his book AlaS Mein Intekhab: Dilli (1987), describes one such Basant in Delhi at the time of Bahadurshah Zafar, in following words:

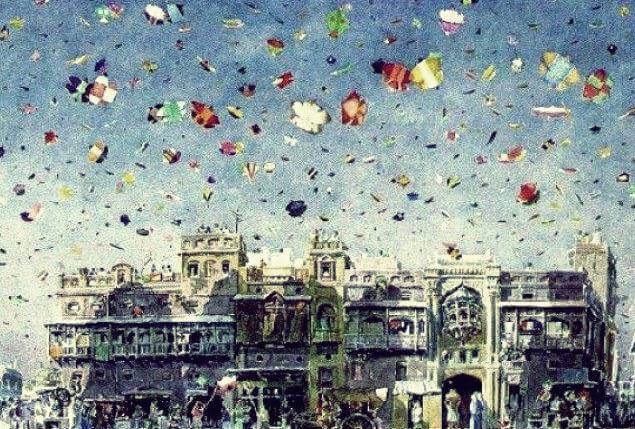

“…the chill was on the decline. The spring had arrived. Dilli wallahs were as usual setting up the fairs for Spring. Many were offering flowers and ittar on the Qadm Sharif (a sacred space in Jama Masjid). When people heard the announcement of Bahadur Shah Zafar s birthday they gushed forth with joy. It was Thursday. There was such a crowd that not a hair s breadth of space was empty either on the Red Fort maidan or the shore of Jamna. The curtains of houses, the Chadurs of women, the turbans of men, and the clothes of children, everything was dyed Basanti – even the candles hanging from the rampart were Basanti. It was as if mustard was growing in every nook and corner. Indoors and outdoors, people danced the whole night. Thousands of giant balloons made of mustard coloured paper, with candles lit inside, were being flown in the air. By four o’clock in the morning the whole sky became Basanti. It seemed as if mustard was flowering in the eyes of the sky .”

Compared to the glitter of Basant in the past what we find today for instance in the Dargah of Nizamuddin at Delhi, seems more ritualistic, nevertheless festive. On Basant Panchmi some qawwals from Dargah go to a nearby Haryana village to collect mustard flowers. On the way back they offer them first on the tombs of many saints related to Nizamuddin Aulia s order, including Naseeruddin Chiraghe-Dehli and others near Mehrauli. Back in Basti Nizamuddin, some interesting rituals take place dyeing of the clothes in the Basanti colour being the most exciting one. One can see hundreds of people wearing Basanti scarves, handkerchiefs, chadurs and caps, almost dancing to the tune of Basanti qawwalis. They offer the flowers and fateha on every little grave present here. The beautiful Hindi and Persian qawwalis sung here – mostly ascribed to Amir Khusro himself – praise the coming of spring and the disciple’s longing to meet his pir.

Sufis have a long tradition of adapting to the local culture and language of the places they travelled to spread their message. The Chishti sufis too, have not only tried to relate to the Indian culture and music, they even experimented and enriched the various cultural forms. Basant is a living example of that. In today’s scenario while communities are being forced to get more and more polarized into their political molds, Muslims celebrating Basant or Hindus taking part in Eid may sound like a dream. In the past it was these Dargahs and Khaneqahs which served as a platform where the twine could meet. Don’t we need the spirit of the dargahs today?

About the Author: Mr. Saeed is a resident of Jamia Nagar, New Delhi, who believes the Internet may be the only medium that allows a free flow of ideas across deep-rooted real-world divisions. Articles first published in Google Groups in 1998 [now defunct], and reproduced with compliments.