Remembering the first Pakistani to win a Nobel Prize: Dr. Abdus Salam – By W. Bokhari

dr-abdus-salam-ravian

I never met Abdus Salam, but at the Abdus Salam International Center for Theoretical Physics (AS-ICTP), where we all convened a year after his death, his presence in spirit was undeniable. We were all there, the “extended family of Salam”, to pay homage to a person who influenced us in different ways: scientists from all around the world who had worked with Salam and who knew Salam as one of the architects of the fundamental laws of physics, scientists from the Third World in particular for whom Salam was like a father figure who helped the spread of science and knowledge in their countries, bureaucrats and government officials with whom he successfully negotiated the inception and funding of AS-ICTP against impossible odds, policy makers who were guided by his far reaching visions for education and development, members of the local government of Trieste who wanted to celebrate the life of their world-famous “adopted” citizen and even the president of Albania, a physics professor, who came to share his experience of Abdus Salam with us. And then there were people like me who understood modern physics in terms of the Electroweak Theory of Salam, Glashow and Weinberg, but never got a chance to work with him. We were attracted by the continuing legacy of Salam -specialized talks on a wide spectrum of research problems at the forefront of physics.

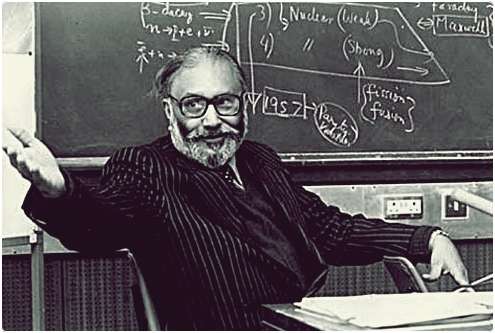

All of us knew that Salam was one of the greatest scientists of this century, but not all of us really appreciated the full extent of his genius. As the conference went along, we were amazed at his versatility and sheer energy. His old colleagues at Imperial College recalled that he was a full-time contributor to the department, supervising five or six students, meeting with them almost daily, and constantly working on new ideas and writing papers. He was a prodigiously productive physicist and a demanding advisor to his students. What they did not realize was that Salam, at the same time, was also the science advisor for President Ayub Khan and was deeply immersed in policy making for Pakistan. During those days, he went on to establish the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission and SUPARCO to name just two. Later on, he also became actively involved in founding an international center for science and technology. Lobbying for what is now AS-ICTP was not easy. He had to deal with procuring funding and support for a project that was deemed unnecessary by many of his Western scientific peers. Some of them actively opposed the idea citing reasons that were blatantly racist. But in the end, the Center was established, and has for more than three decades now, been an unparalleled forum for exchange of ideas and cultures.

As the conference drew to a conclusion, I spent a day in the office of Abdus Salam, going through his collected papers, his books, various news clippings about his life and the letters of condolence sent by people from all across the globe upon his death.

His scientific papers traced the historical route taken by modern physics, which to me was not surprising. He had worked on and made seminal contributions to many key concepts of particle physics -renormalization, parity violation, electroweak unification, supersymmetry, leptoquarks, grand unification and superstrings. His Nobel Prize recognized only one of these: electroweak unification. To call his mind “fecund” would be an understatement -his papers are an irresistable flood of ideas. Many of his colleagues recalled the contagious excitement of Salam whenever he had a new idea, which was very often, probably too often for some. There were no barriers to his mind, Salam was a perennial learner and an ardent student until the sunset of his life. Miguel Virasoro, who succeeded Salam as the director of AS-ICTP, went to visit Salam not long before he died. Salam was very sick, and had extreme difficulty expressing himself. Virasoro decided to tell Salam about his own latest work, not sure whether Salam in his condition would be able to appreciate it. However, as Virasoro spoke, he could see the expressive eyes of Salam reacting to all that he was saying. Once he was done, Salam mustered all of his strength, and said, “But what about gravity?” Even his debilitating terminal illness could not tarnish his exceptional ability to see through to the heart of a problem.

His collection of books encompassed a vast spectrum. Apart from the books on physics, mathematics, biology and other scientific disciplines, he had a collection of books on all the major religions of the world, various philosophical works, works of literature from different cultures, histories of different parts of the world, works on different kinds of policy making and studies of various aspects of societies across the world. In terms of religion and the “metaphysical” aspects of life, it was clear that he had done a thorough comparative study. That gave him an insight into the motivations and desires deep within the human soul. His own personal beliefs gave him a conviction that could guide him through any circumstance. Prominently displayed in his office is a large Arabic inscription “Naad-e-Aliyan Mazhar-ul-Ajaib” or an invocation of the help of Hadrat Ali in the manifestation of miracles. This scientist believed. Also, perhaps it is not surprising that Salam had a passion for literature, the distinction between “science” and “art” is really quite arbitrary, especially for a keen mind as his. His exceptional intellect and his intellectual versatility gave him an understanding of the human side of affairs which is rare, not just in specialized scientists, but in people of all backgrounds. Salam had the tools to perform miracles.

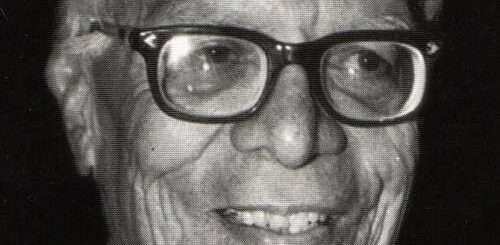

His life, judging from the collection of various news clippings and photographs, had taken him a long way. A small kid in an oversized turban from an unknown village in Punjab had grown to become a maestro who would claim his place in the top echelons of global intellectual community -an elitist community with many subscribers to the colonialistic mindset. As Nigel Calder, the famous science writer from Britain, pointed out, Salam’s life is like “a fantasy straight out of a story-book”. He wished that Pakistani children should grow up reading story books about a hero named Abdus Salam, and through him they would find confidence in their own abilities, and have high aspirations about their own futures. The life of this hero was shaped by a will that could defy all odds. And in the process, he gave a lot in return to others. One of the most poignant moments in Salam’s life was when he had to leave Pakistan in order to pursue his interest in physics. He desired that no young scientist from a Third World country should ever have to make a choice between his homeland and his interest in the sciences. This was one of the causes that he gave to freely. During his life and after his death, people found themselves celebrating his services: little kids in a Peruvian village, who followed him around shouting “El Nobelo, El Nobelo”, scores of awards and honorary degrees from universities and governments throughout the world, his students who went on to found centers of advanced learning throughout the under-previlged parts of the world, Salam-Fest’s organized by scientists, the outpouring of grief over his demise.

At the end of the day, I realized, that for Salam, all of these endeavours and achievements were not an end in themselves, but a means to an end. His life was a manifestation of his convictions and his understanding of his roots.

In the main lecture hall of AS-ICTP, there is a large framed picture entitled “The Silent Genocide”. One half of the picture is a painting which shows a soldier involved in the sacking of a city. His sword is raised high above his head, ready to strike down on a baby lying on the floor. The mother is desperately trying to save her baby by imploring to the soldier. The other half of the picture contains an abstract of Salam’s Red Book , which he used to publish annually under the umbrella of the Third World Academy of Sciences:

This globe of ours is inhabited by two distinct species of humans. According to UNDP count of 1987, one quarter of mankind, some 1.2 billion people are developed. They inhabit two-fifths of the land area of the earth and control 80% of the world’s natural resources, while 3.8 billion developing humans -“Les Miserable” -the “mustazeffin” (the deprived ones) -live on the remaining three-fifths of the globe.

What distinguishes one species of human from the other is the ambition, the power, the elan which basically stems from their differing mastery and utilization of present day Science and Technology.

Salam believed that the present divide between the scientific and technological achievements of the (rich) Northern and (poor) Southern nations was a result of the concentration of economic power in the hands of a few nations after the Industrial Revolution[1]. Even after the dismantling of the colonial empires, and the emerging of the Third World, the situation was not corrected. First of all, the ruthless exploitation of the poor countries continues unchecked in many forms. And second, the widening economic disparity between the rich and the poor also leads to an ever widening scientific and technological gap which in turn further widens the economic gap. This, he believed, constituted “the silent genocide” of the poor by the rich.

In an article titled, “Diseases of the Rich and Diseases of the Poor”, which was published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists in April 1963, he wrote:

Year after year I have seen cotton crop from my village in Pakistan fetch less and less money; year after year imported fertilizer has cost more. My economist friend tells me that terms of trade are against us. Between 1955 and 1962 the commodity prices fell by 7%. In the same period, the manufactured goods went up by 10%. Some courageous men have spoken against this. Paul Hoffman called it a subsidy, a contribution paid by the under-developed countries to the industrialized world. In 1957-58 the under-developed world received a total of $2.4 billion in aid and lost $2 billion in import capacity through paying more for the manufactured goods it buys and getting less for the raw commodities it sells…

…It was in 1956 that I remember I heard for the first time of the scandal of commodity prices -of a continuous downward trend in the prices of what we produced, with violent fluctuations superposed, while industrial prices of goods we imported went equally inexorably up as a consequence of the welfare and security policies the developed countries had instituted within their own societies. All this was called Market Economics. And when we did build up manufacturing industries with expensively imported machinery -for example cotton cloth -stiff tariff barriers were raised against their imports from us. With our cheaper labour, we were accused of unfair practices…

…In 1970, the world’s richest one billion earned an income of $3,000 per person per year; the world’s poorest one billion no more than $100 each. And the awful part of it is that there is absolutely nothing in sight -no mechanisms whatsoever -which can stop this disparity. Development on the traditional pattern -the market economics -is expected to increase the $100 per capita of the poor too all of $103 by 1980, while the $3,000 earned by the rich will grow to $4,000 -that is, an increase of $3 against $1,000 over an entire decade.

Salam believed there were two necessary steps to stop this ever-growing disparity between the rich and the poor. First, a dedicated system of aid from the rich countries to the poor. This aid would not only foster economic growth and inter-dependence between the rich and the poor (with benefits to both), but also compensate for the past and present exploitation of the poor countries. It would also account for the unequal distribution of natural resources between the rich and the poor. Linus Pauling, twice Nobel laureate, had initially sketched out a scheme at the Nobel Symposioum in 1969. He had suggested a transfer of $200 billion per year from the rich to the poor countries, roughly 8% of then world GDP and suggested heavy cut-backs in the defense spending around the world, to free resources for global development. Pauling’s proposal in turn inspired Salam to espouse the same idea. Unfortunately, Pauling’s idea was deemed too idealistic for implementation at the time, even though it won many advocates within and outside scientific circles.

The second necessary step, was sketched out by Salam in his address at the 13th Annual All-Pakistan Science Conference in Dhaka (1961) [emphasis added by the author]:

I have mentioned technological skills and capital as the two pre-requisites before a pre-industrial society like ours can crash through the poverty barrier. Actually there is a third and even more important pre-requisite. And that is the National Resolve to do so. In Professor Rostow’s words, nation’s take off into sustained growth awaits not only the buildup of social overhead capital -capital invested in communication networks, schools, technical institutes … but it also needs the emergence to political power of a group prepared to regard the modernization of the economy as a serious high order political business. Such was the case with Germany with the revolution in 1848, such was the case with Japan with the Meiji Restoration of 1868, such was the case with Russian and Chinese Revolutions. Our independence in 1947 did not -definitely did not -coincide with the emergence of a political class which made economic growth the center piece of state policy. I can still recall the interminable arguments, conducted in private and public, in the early years of Pakistan about ideology. Never did I hear the mention of total eradication of poverty as one of the priority ideological functions of the new State.

To Salam, poverty was “synonymous with kufr”, or a heinous sin. Poverty is engendered by population explosion and depletion of global resources. Poverty in turn causes the decline of science and technology and further widens the gap between the rich and the poor. Eradication of poverty, therefore, has to be a part of the state policy.

Today, as we remember Abdus Salam, we realize the long road Pakistan has travelled in the last 50 years. There have been many successes and many failures. If Salam were to return to his small village close to Jhang today, he would probably notice that a lot has changed since he first left his village about sixty years ago. On the other hand, he would also bemoan the fact that not enough has changed, and that we could have done much better. Perhaps, the best way to remember Salam is then to learn from what we have experienced as a nation, and understand that our collective will as a nation is an agent of change, and we have to exercise our will to improve our lot. If for no other reason, at least for all the Abdus Salams, born in the backward areas of Pakistan, who are mercilessly devoured by poverty.

References:

Abdus Salam -A biography by Jagjit Singh, Penguin Books, 1992.