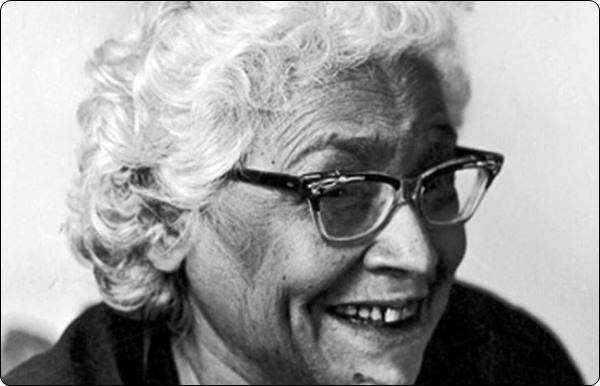

Ismat Chughtai’s Autobiography – A Translation by Muniba Kamal

Ismat Chughtai’s Autobiography — A Translation by Muniba Kamal

About Ismat Chughtai

Born in 1915, Ismat Chughtai was a bold daughter of Independence. Though she came from a conservative family, she was probably Urdu’s most outspoken female writer at the time. She was briefly associated with the Progressive Writers’ Movement in Lucknow. An intense individualist and iconoclast, her output was prolific. A master storyteller, she writes simply, vividly and more often than not shockingly. Her candour stretches from her fiction into this essay. Here she traces the events that made her what she was – a woman living within the confines of a conservative society with the will power to over ride conventions and shape her own destiny.

My Autobiography (translation of an Ismat Chughtai essay)

When I seek out my first visual memory, a round room with red glowing mirrors revolves before my eyes where I roamed about clapping my hands. This glass chamber was my mother’s womb. Till today, I can still see her womb as this room sometimes. Then there is another circumference I remember where people are running circles around me while I stand in the middle dressed in resplendent finery. I recall myself dancing at my uncle’s wedding. People are standing all around, yet it seems that they were going round and round. Even today I have a feeling that they were moving while I stood still.

We had a white mare at home. All my brothers took turns riding her. The groom would take them around. I watched them with envious eyes and begged for a turn on the mare with wilful petulance. But my mother wouldn’t hear of it. (Girls are not supposed to ride horses). ” If you get on that horse I will break your legs,” she warned me. Whenever I saw any of my brothers proudly astride the white mare, I wanted to burst into tears.

Once I was crying as I followed the mare around. One of my brothers was sitting haughtily on her. At that moment my father returned from the District Court.

“Why is she crying,” he asked the groom.

“She wants to sit on the horse,” he replied.

“So why don’t you let her sit,” inquired my father.

“Sir, I don’t have Madam’s permission,” explained the groom.

“Let her,” said my father.

After this exchange, I was to sit on the white mare everyday. Sitting on her, I felt overwhelmed by victory. It was the first conquest of Ismat the rebel. Subsequently, when my father took my brothers out for target practice, he would place the gun in my hand and teach me how to aim and fire too.

I was the tenth child born to my parents. After my birth, my mother lost interest in children altogether. I remember that the nanny and my elder sister looked after me. The nanny left after two or three years. I remember she had a certain way of sitting with her head turned to one side. I could clearly see her green silhouette. Baji took great care of me. Wrapped around her legs all day, I used to feel that I was safe. There is a possibility that my mother hated me. She had a child every two years. God bless the monkey who in those days helped family planning on its way. It happened when Mother was in the family way. A bowl of grams perched on her pregnant stomach, she was chewing away under a tree. A fat monkey sitting on the branch above her felt like having some grams too. He leapt onto her stomach from a great height. Mother miscarried and never had a child again.

I was four years old when Baji got married. A tall, skinny bridegroom whose festive garlands I badly wanted to tear off took her away. He was an S. H. O. Everybody at home, young and small, used to tease me by chanting:

Baji’s toe rings are grainy and she has been taken away by a policeman.

I saw my howls dissolve in the noise made by the wedding band. Baji left home. What impact does the crying of a child have in this pandemonium? In those days, I sometimes dreamt of a young girl shedding tears as she slowly made her way down a dark empty street. She was I.

There was a huge age difference between myself and the rest of my sisters. They used to form a cluster in a corner and gossip about their respective fiances. Whenever I approached them, they shooed me away. My brothers were engrossed in their own fun and games. I was without company, that is, free. Nobody would tolerate my coming within the radius of their party.

Slowly I began to understand that climbing a guava tree is better than joining your head with another and talking senselessly like my sisters. It is more interesting to see a performing monkey than standing on the servants’ heads while they cook in the kitchen. And it is easier to run after chickens than to wrack your brains and come up with more things to add to your trousseau. I have always taken the other way and I continue to walk on this path today. Who in my house was worried about how I was growing up? With my brothers, I played all the games that boys play. I turned twelve playing gilli danda, flying kites and kicking a football. By that time, as far as reciting goes, I had finished reading the Koran. Instead of congratulating me, everybody said: “Look, she’s finished the Koran too late. She is so old. Her niece is five. She has finished the Koran and she also knows how to sew.” This niece was my favourite sister’s daughter who was now a widow. Now I remember how an incoming telegram caused a furore in the house. My brother-in-law had passed away. I was happy because I thought that Baji would come back home. No longer would I dream of that little girl all alone on a dark street. But then I discovered that it was another sister’s husband who had died. But then again, when was God ever interested in me?

When I turned twelve my mother dug out an old gharara and told me to make a drawstring for it. “Your hand will get better at it,” she remarked placing the needle and thread in my palm. She watched me sew. I felt as if I was suffocating. When I saw my brothers running after the chickens and climbing trees, the needle would prick me and draw blood. Thankfully Mother had a lot of housework to take care of. Whenever someone beckoned her I would shove my unfinished handiwork between the folds of the quilts on the shelf. When winter arrived and they were unfolded, my needlework came tumbling down.

Then my mother wanted to teach me how to cook.

“I won’t learn,” I insisted.

“Why not?” asked my mother.

“Why doesn’t Shahnaz Bhai learn how to cook?” I counter-questioned.

“When he brings his wife home, she will cook for him,” she replied.

“Who will cook for him if she dies or runs away?” I inquired.

Shahnaz Bhai burst into tears at the suggestion that his wife would run away. At this point, my father entered the room.

“Women cook food Ismat. When you go to your in-laws what will you feed them?” he asked gently after the crisis was explained to him.

“If my husband is poor, then we will make khichdi and eat it and if he is rich, we will hire a cook,” I answered.

My father realised his daughter was a terror and that there wasn’t a thing he could do about it.

“What do you want to do then?” he asked.

“All my brothers study. I will study too,” I said.

My uncle was assigned the job of teaching me. After a month of extensive study, day and night, I was accepted into the fourth grade at a local school. After that I got a double promotion and was promoted to grade six. I wanted to be free and without an education, a woman cannot have freedom. When an uneducated woman gets married, her husband addresses her as “stupid” or “illiterate”. When he leaves for work, she sits at home and waits for him to come back. I thought that no matter what happens, I would never be intimidated by anyone. I would learn as quickly as I could.

I didn’t want to get married. Well, I did fancy a boy in the neighbourhood. I was twelve or thirteen at the time. That is the age when age love starts making a home for itself in a girl’s heart. The gentleman must have been twenty-six years old at that time. He lived next to our bunglaow. He would go riding early in the morning. To sit and watch him go riding became a daily ritual. I don’t think he ever thought that this little girl was crazy about him. He was very handsome. But why would he have looked my way? His eye must have been set on someone his own age. All I did was watch him go about his way on his horse. And that was how it was till I met him on Shahid Latif’s film set thirty years later. On recognising me, he gave me a hug. ” Oh scoundrel!” I thought in my heart of hearts, “What’s the use now? If you had held me this close thirty years ago, what wouldn’t have happened in my world? You didn’t notice me then. When I had filled all thirteen years of my life with love for you and showered it all on you.” Till today the thought of that handsome prince can make me feel romantic – that scoundrel who dried my youth.

There were quite a few likeable boys at school, but I was only enamoured by a couple of days. Girls would swoon over the good-looking and capable boys. The skinny, deathly, limp-as-a-dishrag types would run after the girls. There was one really handsome Christian boy who was the centre of attention of the girls. I was friendly with him too. All the girls would go to his house and feast on cakes and pastries. In those days our college just had female students. But whenever a leader came, like Maulana Azad, Nehruji or Vijay Lakshmi Pandit, they would give a lecture at the university. Then we would also go to the boys’ university to hear them. The boys would be seated like gentlemen on the benches in the hall. They would turn into hooligans the minute they stepped out on to the street. Walking along the railway tracks opposite the building, they would hurl abuses, laugh at nothing in particular and fall over each other while walking. The girls trudged all the way to their hostel, eyes downcast. This drama would always agitate me.

Our teachers were under the impression that boys get a real kick out of us girls talking to them. I would say to the girls: “These boys want to be friends with us. They won’t eat us. Why don’t we befriend them?” But none of the girls agreed with me.

One day after a lecture girls and boys were walking on their respective sides of the railway track. All of a sudden, a boy recited a couplet loudly. I couldn’t resist tossing a question his way.

” Is that Jigar’s couplet?” I asked.

The boy looked from left to right trying to place the voice. He was taken aback by the fact that it belonged to a woman. I repeated my query.

“I don’t know,” he stammered.

“Why are you shooting arrows in the dark? This couplet was written by Daagh,” I said, upon which I turned to the girls with the words, ” Look nobody ate me up. I am still alive.”

After this incident we became friends with quite a few boys. Together we would speak of books and poetry. Of course three or four girls would get the boys to buy us tea. We would know what to order even before we met them. Sodas, samosas and potato cutlets would do rounds. We shared all the goodies the boys were sent from home filled with mangoes and sweet meats. If the teachers got upset, they would get a mango as well.

Once we were headed home for the holidays. The boys were on the same train. Whenever we stopped at a station, the boys would come and stand next to our carriage. Scared, the girls remained inside and looked longingly at all the things being sold on the platform. Nobody had enough bravado to go out and buy something. We were dying of thirst. I knew that the journey was going to be very unpleasant. At the next stop, I yelled out to a boy on the platform: ” Oye, come here for a second.”

He didn’t understand. I signalled him again.

He came up to the window rather nervously.

“Will you get me a soda?” I asked.

“Of course,” he said.

In the wink of an eye there was a bottle in my hand. I offered him some money, but he refused.

“Why should I expect you to pay for my soda when you have done me a favour by getting it for me?” I asked handing him the money.

When the train started moving, the teacher got mad at me for asking a boy to get me a soda.

“If he comes again I will ask him to get food for me too. I just spoke to him. Is there something wrong with that? At the next station I will get you a soda too,” I retaliated.

The teacher didn’t take to kindly to this, but at the next station, the boys came again. Whenever the train approached a platform, we would ask them to get something for us. We became quite comfortable with the boys and the journey passed pleasantly.

I used to sleepwalk as a child. This habit continued till I was ten or twelve. Once I lifted the latch and went into the garden. When I woke up I was standing under a tree that we used to call the demon tree. I didn’t see a demon or any other like creature, but my mother believed that a one had possessed me. She went to a shrine, made offerings for my well being, got a stick from there and hit me on the head with it to chase the spirit away. The demon wasn’t there. The demon didn’t go. Even evil spirits knew better than to possess me.

When I was in grade nine, marriage proposals started coming for me. My mother decided that she would give her youngest daughter hand in marriage to a deputy collector. Tailors and jewellers came and sat at our house. When I came home from school one day and saw the milieu, I got suspicious. I didn’t have any unmarried sisters left, so what was this hullabaloo about? Investigating further, I discovered that the preparations were for my wedding. I got worried.

“I won’t get married. I will study,” I said insistently to both my parents.

“She’s mad,” my mother proclaimed.

“Who says don’t study? You can study at your in-laws place,” explained my father.

“As if anybody can study at their husband’s house,” I thought. “If the collector is anything like my father, what will I do? Produce a kid every year or give exams.”

After giving the problem much thought, I hit upon a solution. My uncle’s son was the answer. He was studying medicine in Bombay. I wrote him a letter.

“You are the only one who can get me out of this fix and you don’t even have to do anything. All you have to do is write a letter to your father saying that you like me and want to marry me. This is the only thing that can stop my wedding. I swear by the Koran, Allah and my education that I will never marry you. Please do this deed in the name of God. Please stop this marriage from happening.”

My cousin abided by my strategy. A couple of days later while my mother was bargaining with the painters, my uncle came in all in a hurried flurry.

“Shaukat likes Ismat. You cannot give her to an outsider. Read this letter,” he muttered.

My mother beamed from ear to ear. The tailors and jewellers left leaving unstitched clothes and molten gold behind. My impending marriage was put on hold – indefinitely.

When I was young, we were carted to school in a dilapidated car with curtains. A woman would chaperone us, scolding if we took a peak through the windows. We remained in Aligarh until I completed my metric. After that I went to Lucknow and stayed at a university.

As a child I went out in a phaeton, always accompanied by my mother. In those days all carriages were curtained. I was told to wear a burqa while still in school. Wait, now I remember, once we were travelling by rail. Before reaching the destination all women put their burqas by their side. I knew that I would have to don my burqa as soon as we stepped down the train. When the servants started to tie up the mattresses, I hid my burqa in one of them. Soon the offending cloth was tied up in between one of eight mattresses. When the train stopped, I started looking for my burqa innocently.

Everybody said: “After all, where can it have gone?”

“You rogue. You haven’t thrown it off the train have you?” exclaimed my mother.

After receiving a couple of blows on my back, I said with an air of deep thought: “Maybe it’s tied up in one of the mattresses. I remember putting it under a pillow.”

Now nothing could be done. It had taken two hours to tie up the mattresses. It would have taken one hour to untie them. I left the train without wearing a burqa for the first time as an adult.

Once my father asked me, “Do you keep your head covered in school?”

“No. I think I look downright stupid with my head covered,” I replied.

Abba grunted in surprise.

I discarded the veil. If I really needed to cover myself, I would borrow a burqa from some old woman. Anyway, by the time my father retired and returned to Lucknow, all women had to discard the burqa. What happened was that in Jodhpur, Hindu women wore a chaadar. All the rogues sitting on the village pavilion kept an eye out for them. They followed them and gained a thorough knowledge of the women’s whereabouts. There was a furore in the neighbourhood. The general consensus was that Muslim women would also don a chaadar like their Hindu counterparts. Nobody would know the difference. The problem would be solved because the only way to identify a Muslim woman was by her burqa. After that everyone in my family discarded the veil. I had come out of purdah by the time I reached college. When I had to go to university, I would make do with a borrowed one. After that I started wearing khaddar.

Khaddar came into vogue when Gandhiji visited Lukhnow. Some of us girls went to visit him. When we asked for his autograph, he said: “All of you wear khaddar and come, then you will get my autograph.” We all bought khaddar that evening. The next day thirty girls clad in smelly, rough, starched khaddar dhotis went to give homage in Gandhi’s court. Gandhi toothless grin seemed to be saying: “Look, I have made thirty girls wear foreign clothes.” He made us sit by his side with humorous affection and gave us autographs. Once I almost got arrested because of my penchant for khaddar.

I was working then and was en route to Jodhpur to visit my mother. I spent the day in third class, but booked a cabin in first class to sleep in for the night. I was wearing a khaddar dhoti.

In Phulera, two stations before Jodhpur, the news spread that a high level member of congress is on board. In those days members of the Congress were banned in Jodhpur. When I stepped onto the platform clad in a bright white khaddar dhoti and a pair of spectacles with a bag dangling on one shoulder, I found the police standing there to welcome me. By coincidence, the sub inspector was my uncle. He was quite dazed to see me instead of a Congress leader.

“This is my niece,” he blustered in surprise .He was quiet on the way home, but as soon as we entered the house he turned on me. “You shameless, ill-mannered wench. What is all this about?” he roared.

Feigning an air of nonchalance I said: “What? I am just wearing a khaddar saree. I havent done anything.” Because I had a job and was supporting myself, nobody could argue with me.

There was a vacancy for a headmistress in Jodhpur at the time. I was the only B.A.B.T pass Muslim girl there. “Muslims must have their rights” was the slogan and I got my right. I became headmistress of the school. I wore a chaddar when going there.

“You should wear a burqa,” an uncle said.

“You’re joking,” I scoffed and left the house in a chaddar saying, ” If you tell me to wear a burqa again I will resign.”

Everybody was aware of my stubborn streak. Nobody said anything. When my father had refused to let me study beyond matric, I threatened him.

“If you don’t let me study further, I will go to a mission and convert to Christianity,” I said.

“How will you go there?” he asked.

“I will walk along the railway track. I know the way. They will convert me, take me away and admit me to one of their schools,” I replied.

Father came round to paying for my higher education. He saw that my heart was set on studying and that marriage was not in the wings as far as I was concerned. He put a small house in Agra in my name. It was worth three or four thousand rupees then. I left the house to my brother for safekeeping. I thought I would sell the house, leave for England and find a better job there. So I left for my brother’s house in Agra.

“Please help me sell my house. I want to go to England,” I voiced my intentions.

“What house?” asked my brother. “That house with the mare? Oh, we faked your signature and sold it off a long time ago. What little money was left, was spent in making jewellery for your bhabhi.”

“Ay hai, don’t drag me into this,” said Bhabhi. “How am I supposed to know where the money went?”

I was fuming with anger. “Bhai jaan, I can file a case against you,” I stated.

“Of course you can. I might even go to jail, but you still won’t get the money,” he retorted.

“You are a lawyer. Tell me, how do I go about filing a case against you?” I asked.

“I can fight a case for you, but you will have to give me an advance now,” he replied.

Hearing this, my bhabhi started panicking, but my brother ignored her and asked me gently: “Do you really want to go to England?”

“I really do,” I said.

“Then swim there,” he replied.

He proceeded to explain the way from Bombay. “Rest here for two days. Then swim. You will get to England in a few days.”

His wife was listening to this discussion with rapt attention. “What will happen about her clothes?” she asked

“She can sew them into an oilcloth and tie the packet on her stomach. What else?” my brother replied.

Then bhabhi raised another pertinent question. “There are lots of big fish in the sea. Won’t they eat her?”

“Keep a big bamboo stick in your hand. You can ward of the fish with it,” my brother advised.

My nephew was also sitting there listening to what was being said.

“Foo Foo, I will come with you too,” he lisped.

As soon as he entered the conversation, my trip to England ended.

I have broken chains every step of the way. Opposition parties have made a big hoo ha, but heaven has always been mine.

I met Shahid Latif for the first time in Aligarh. He was doing his M.A at the time and I was doing my B.T. Then I once had a cursory meeting with him in my heart. After that he came to Bombay and joined Bombay Talkies as a scriptwriter for the sum of 225 rupees. I met him again when I came to Bombay as school inspector and started living with my brother. He started visiting our house. I went out with him. We would watch films together, walk barefoot on the beach and meet other literary friends.

Once Shahid took my stories to sell to Bombay Talkies. Someone told my brother about it and he got very angry. He thought that since his sister earned three hundred rupees a month, she should get married to someone earning 1500 rupees at least. He didn’t like my consorting with a scriptwriter who earned a pittance of only 225 rupees a month. When I saw that my freedom was being restricted, I left his house and started living in a hostel. My brother then started pestering my cousin who had stopped my wedding.

“You are still single. Ask Ismat to marry you. She might say yes,” he said to my cousin.

So one day, my cousin came to the house.

“Will you come to Chowpatti with me?” he asked.

“Of course I will,” I said, rather taken aback.

After wandering around Chowpatti, he wavered a bit and said: “Bhai has said, that if you want you can marry me.”

“God forbid. You have done so much good for me in life. Why should I take on this enmity with you?” I asked. Then I added with more sobriety: “The wife I imagine for you in my mind isn’t me. It is a very beautiful, pure and innocent young girl.”

We came back home. I was just friends with Shahid then. Our marriage owed more to confusion than anything else. Khawaja Ahmad Abbas got us a flat near his house. Mohsin got hold of a Qazi and so the marriage took place. I explained to Shahid before getting married to him that I am a troublesome woman. That I have broken chains all my life and I would never be able to stay bound in them. To be an obedient blameless wife was a role not suited to me. Shahid didn’t listen to me. When we were friends, he claimed he would marry me. Everybody would laugh out loud at this. This seemed to make his resolve even stronger.

One day before the wedding, I warned him for the last time: “There is still time. Listen to me. We can be friends forever. I am telling you this as a friend.” He didn’t listen. I thought in the secret heart of my hearts: “You will remember later that a friend gave you some sound advice that you didn’t take.” Even after we got married, I told him once: “There is no compulsion. If it doesn’t work, divorce me.” Shahid thought that if he ever divorced me, people would think that I was the one to leave him and run away.

My older brother didn’t attend the wedding. He didn’t see my face until the day he died. Yes, when Mother found out, she sent my younger brother to Bombay to find out what her problem child was up to.

When all six feet three inches of my younger brother exchanged pleasantries with Shahid, he took me aside and said: “What are you doing? He is such an innocent looking man. He is going to marry you? Has your mind run away?”

“He doesn’t listen to me. I have told him not to. Now you can try too as well,” I said with all the nonchalance I could muster.

Shahid kept me very happy. He was obsessed with buying books. He used to bring very good literature home. Whenever a new novel was published, he would buy it and bring it back. Till today all the books I own have been bought by him.

Man is ready to worship Woman to the extent of making a goddess of her. He loves her. He respects her. But he cannot give her a reason to be his equal. What a beautiful thing man understands. How can one be a friend to an illiterate woman? But then, friendship needs love, not education. Or does it?

Shahid treated me as an equal. That is why we lived a happy married life.