A Glimpse Into Life In Pakistan on Celluloid – By Shoma Chatterji

Despite the brouhaha around Pakistani politics, cricket and film stars, it is strange that as Indians, we do not have even a nodding acquaintance with Pakistani cinema.

Despite the brouhaha around Pakistani politics, cricket and film stars, it is strange that as Indians, we do not have even a nodding acquaintance with Pakistani cinema. Khamosh Paani is the first Pakistani feature film this reviewer got to see. Khamosh Paani won the Golden Leopard at the 56th Locarno Film Festival, Switzerland, in 2003, competing with 19 films from 17 countries. You know why when you see the film.

The strongest point about Khamosh Pani is that it defies any given genre. Opening around 1979-80 when Bhutto was hanged during Zia-Ul-Haq’s martial rule, the film, a Pakistani-German-French production, flits back and forth between 1947, when Pakistan was born, and 1980, when the film opens. The film closes in 2002. There is a well in Charkhi, a peaceful farming village far away from the nearest big city Rawalpindi, where village women draw their water from. But Ayesha, a widow with a growing son, never goes to the well and has the water brought to her door by a young mother-and-daughter pair. Why? The answer to this question forms the crux of the film.

Debut director Sabiha Sumerr draws her audience into a state of suspension between question and answer, between anticipation and resolution, between alternative answers to the questions posed, between ambivalent emotions and sympathies that are aroused by a suspenseful situation. Her low-key, subtle treatment of the flashbacks and flash-forwards contributes to the specially charged world of divisive, fundamentalist politics traced through the tragedy and anguish of a single woman. Ayesha’s life is a needless struggle with a sense of confused identity heightened by the reality of repeated rejection.

Pinjar, based on an Amrita Pritam novel, has the extra element of a conflict between Muslims and Hindus. The film portrays this with the required sensitivity. Set in the 1940s, it offers something slightly different by focusing on what women and young girls had to go through during that traumatic period. They went through changes that deeply affected their entire lives.

Ramchand Pakistani is more about the coming of age of a boy in adverse circumstances than about the constant war between people of two neighbouring countries. It tells a compelling story culled from today’s headlines and proves that change is indeed the cornerstone of Pakistani cinema. It points out the commonality between the people of two nations. Unlike Gadar, there is no jingoism, no piggyback riding on the fires that continue to plague the politics of two countries bled by the Partition. It is a path-breaking film. It is the first ever film from Pakistan made by a Pakistani producer and director, in which the main characters are from Pakistan’s minority Hindu community. The film is based on a real-life case about a Pakistani father-son duo who spent years in an Indian prison because they were mistaken for spies.

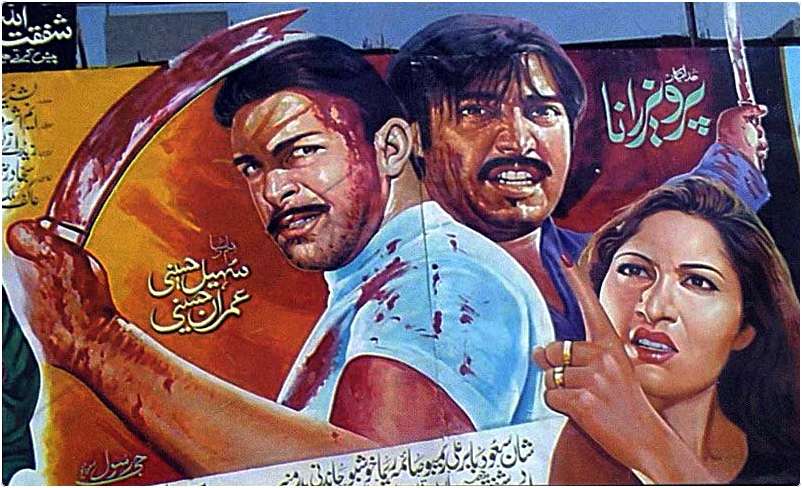

Gadar brought back memories of pulp fiction that became Pakistan-bashing statements on celluloid, loud, crude and forgettable. Gadar portrayed a turban-clad Sunny Deol. With his rippling muscles under a bloodstained kurta, he runs atop a speeding train to shoot down one helicopter after another with that telltale green star and crescent with his single AK-47 as the Pakistani train rushes towards the Indian border. Gadar is no film that will reinforce the harmony that should sustain between the two countries. But with the ticket counters jingled away, merrily unconcerned about the emotional hurt it created in families with members who belong to neighbouring countries, in couples who have undergone an intercommunal marriage. If the box office spelt money for the producer, director, distributors and exhibitors, who would bother about peace and harmony between India and Pakistan? The thumping box office success of Gadar brought in its wake, a jingoistic variety of colourful anti-Pakistani films. Gadar could have drawn from cinema’s potential to tackle a fragile issue like the searing of souls through Partition. But Anil Sharma chose to showcase the macho hero’s superman-like charisma, gained through blood, deaths and violence. Gadar was inflammatory even with in its lyrics and dialogues. It put off Pakistani fans so much that the VCDs nd DVDs of the film could be sold only under the table.

Films like Border, Hero, Mission Kashmir, Zameen, LOC, became Bollywood’s favourite bogeyman. A runaway hit like JP Dutta’s Border did not have a single Muslim soldier in the regiment fighting the Pakistanis. How ethical was it to release the film when Hindu-Muslim relations in India were strained? How humane is it to depict Muslims on both sides of the border as cowards and traitors? Yash Chopra did no differently with his much-hyped Fanah. It is sad to see a terrorist with his own politically brainwashed agenda turn into a cold-blooded killer to save his skin when death finally haunts him. This was not needed as the brainwashing includes the imbibing of popping in the death pill at the point of capture!

Aijaz Gul, my journalist friend from Pakistan, is vociferous in his critique of Paki-bashing Indian films. “Veer Zara from the Yash Chopra stable had dozens of technical and production bloomers. No judge stands up in the court and starts clapping for the hero. Chopra should have hired a consultant from Pakistan to show how Pakistan is today. If this was not possible, he should have hired someone from the Pakistan High Commission as consultant and even if that was not possible, he should have called an overseas Pakistani from USA or UK who visits Pakistan regularly. Adab and sherwanis(long waistcoat) are passe in Pakistan. The Pakistani court erected in the studios left a lot to be desired. It was funny,” says Gul who is planning a book called Bollywood-across the Border. He will invest the book with his 30-years of interaction with Indian films as a journalist. “Veer-Zara is my tribute to the oneness of people on both sides of the border,” said Yash Chopra. He either did not realise that the film was one more addition to the jingoism going under the name of patriotism, or, he was just playing to the gallery, like the film he made. Jingoism brings in money. But it unmakes history and destroys possibilities of peace and harmony between two nations whose people, after one, are the same and want peace and harmony between and among fellow-beings.